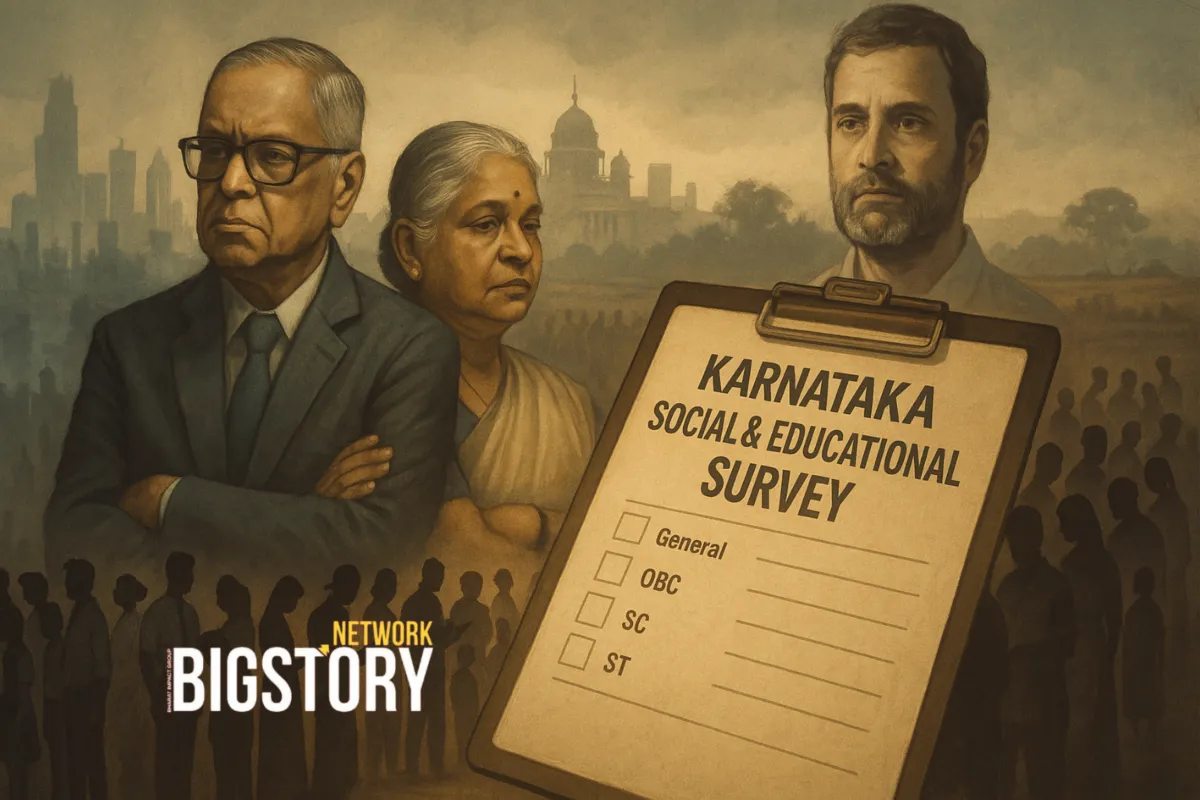

Enumerators from Karnataka’s Social and Educational Survey visited the Jayanagar residence of N. R. Narayana Murthy and Sudha Murty on October 10, 2025. The couple declined to participate in the 60-question survey and submitted a signed declaration.

“We and our family will not participate in the census, and we are confirming it through this letter,” the couple stated. “We do not belong to any backward class. Hence, participating in this survey will not be of any help to the government. Therefore, we decline to participate.”

Their decision drew immediate national attention. The survey is voluntary, but the refusal by two prominent public figures has become a focal point in the ongoing debate about caste data, privacy, and representation in India.

A Legal Right, a Political Flashpoint

Deputy Chief Minister D. K. Shivakumar responded by saying, “We can’t force anyone to participate.” His statement aligns with a Karnataka High Court order clarifying that participation is voluntary and the data collected must remain confidential.

However, the refusal has prompted discussions about how participation in such exercises differs depending on social and economic status. While some groups depend on caste enumeration to access welfare schemes and reservations, others may view it as unnecessary or intrusive.

A Longstanding Position on Reservations

Narayana Murthy has previously expressed his position on affirmative action. In 2003, he said, “Reservations in education and employment should be based on economic criteria and not caste. It doesn’t matter to what caste an individual belongs, as long as such a person or his/her family is handicapped because of resources.”

He has also stated that private sector companies should support inclusion through training and skill development rather than mandatory quotas. Nandan Nilekani, his co-founder and former head of the UIDAI, made a similar argument in 2014: “When it comes to the private sector, we should encourage private companies to themselves be more proactive about inclusion, and not over-regulate them.”

These statements have shaped the public understanding of how the Infosys founders view caste-based policies: favoring economic criteria and voluntary inclusion rather than legal mandates.

The Survey and Its Controversies

The Karnataka Social and Educational Survey is one of the state’s largest attempts in decades to map caste and socio-economic demographics. It includes questions on income, caste, assets, education, and health.

The exercise has faced opposition from several quarters. Some groups have called the questionnaire too intrusive, pointing to questions about gold jewelry, livestock, and personal assets. Deputy CM Shivakumar himself said, “Is there a need to ask about cattle, poultry, tractor, court cases and diseases? Make it simple.”

Dominant caste groups such as Vokkaligas and Lingayats have raised concerns that the survey could reveal overrepresentation in certain sectors. BJP leaders have criticized it as “divisive” and alleged it could be politically misused.

Bengaluru’s Uneven Participation

Urban response to the survey has been notably lower than in rural areas. As of early October, around 83 percent of households statewide had been covered, but Bengaluru’s completion rate remained lower, with officials citing skepticism among urban residents.

Shivakumar later said, “I have told officials not to ask people in Bengaluru about how many chicken, sheep and goat people are rearing, and how much gold they have. They are personal matters.” This statement was widely interpreted as an acknowledgment of urban resistance to detailed questioning.

The Broader Context

Caste data collection has historically focused on Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes to determine eligibility for government benefits. Upper-caste participation has been less emphasized, as these groups generally do not qualify for reservations.

Some policy experts have argued that comprehensive data—including on forward caste groups—can help paint a clearer picture of socio-economic distribution in the state. Others contend that making participation voluntary respects privacy and personal choice.

Technology, Data, and Policy

Co-founder Nandan Nilekani’s leadership of Aadhaar, India’s digital ID program, is also part of this debate. Aadhaar deliberately excluded caste data. Supporters viewed this as a way to move toward identity systems not based on social categories. Critics argue that excluding caste makes it harder to detect and address disparities that persist in hiring, credit, and welfare systems.

What Happens Next

The Karnataka government has extended the survey deadline in Bengaluru to increase participation. The state says the data will be used to inform welfare programs and resource allocation. However, the refusal of high-profile figures like the Murthys has raised questions about the accuracy and completeness of the dataset.

The debate now revolves around two competing principles: the right to privacy and the need for comprehensive data to guide social policy. One side sees participation as a civic contribution to understanding inequality. The other sees the survey as a matter of personal choice.

Leave a Reply