A hard-hitting investigation into Q-Commerce, exposing the economics, psychology, and human cost behind Blinkit, Zepto and Swiggy’s 10-minute delivery war.

Minaketan Mishra

Minaketan Mishra

It was sold to you as convenience.

It evolved into dependence.

Now, it’s an addiction being subsidized by billions of dollars in venture capital — not to improve your life, but to engineer your behavior.

The “Quick Commerce” (Q-Commerce) sector in India — valued at over $5 billion — is celebrated as the greatest logistics achievement of our era. In reality, it’s a financial war where profitability is a rounding error, riders are disposable, and the real casualty is the neighborhood economy.

This is not another feel-good tech success story.

This is a forensic breakdown of how Blinkit, Zepto, and Swiggy Instamart are actively rewriting consumer psychology and government policy to win a war where only one side can survive.

Q-Commerce didn’t emerge by inspiration — it emerged by desperation.

Before Blinkit was the crown jewel of instant delivery, it was Grofers, a confused grocery marketplace founded in 2013. For eight years it failed to beat BigBasket on “next-day delivery” and bled money.

The Pivot: In late 2021, facing extinction, CEO Albinder Dhindsa rebranded Grofers to Blinkit and went all-in on 10-minute delivery.

Zomato acquired it for ~$568M — a “distress sale” that later turned out to be the steal of the decade.

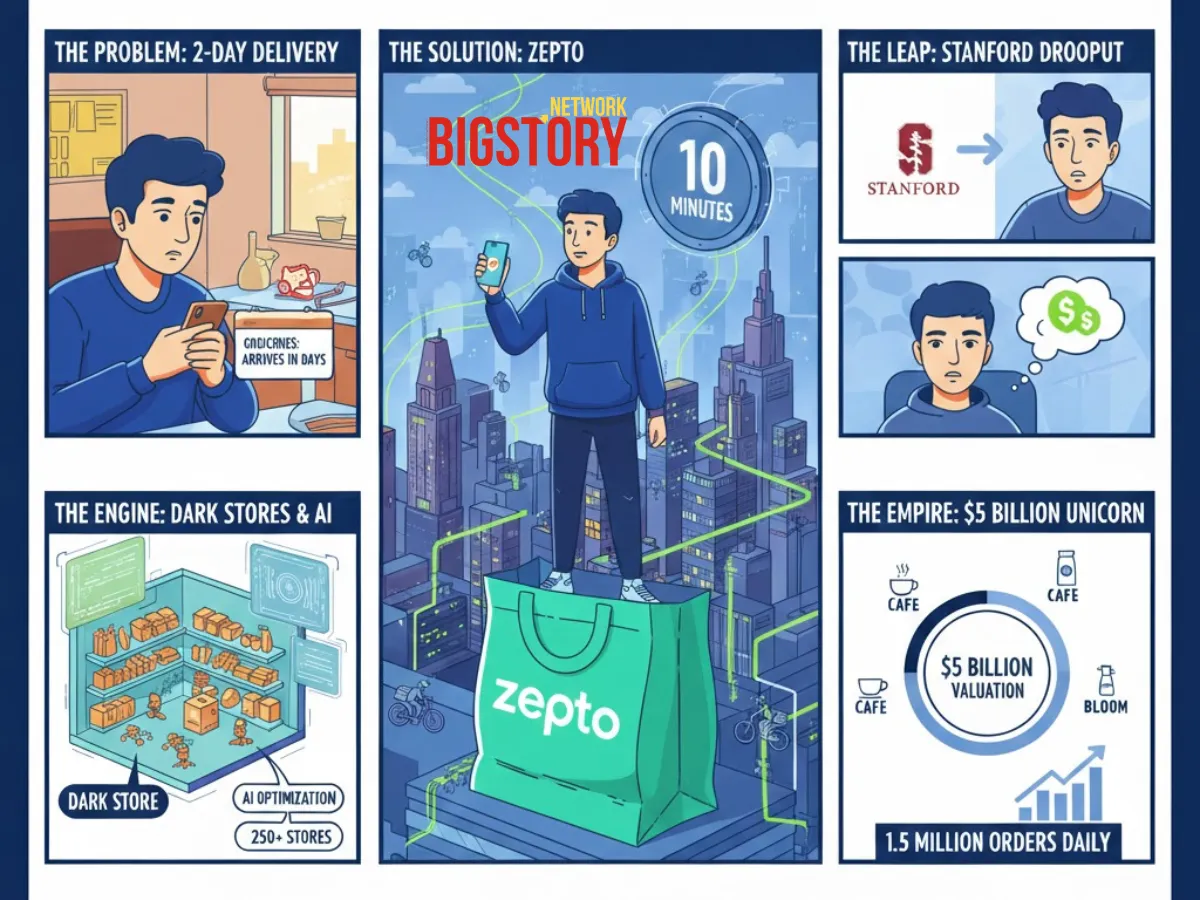

Two 19-year-old Stanford dropouts, Aadit Palicha and Kaivalya Vohra, trapped in Mumbai during the pandemic, didn’t want groceries tomorrow — they wanted them now. They launched Zepto (originally KiranaKart) with one non-negotiable objective: speed at any cost.

Their innovation wasn’t tech — it was supply chain aggression.

Swiggy launched Instamart in 2020, but treated it like a side quest until it realized something shocking:

A bag of chips in 10 minutes is more habit-forming than biryani in 40.

I still remember February last year — the first Swiggy dark store opened near my apartment in Bhubaneswar.

I wasn’t testing a product; I was being conditioned.

The “once in a while” order quietly became 3–4 orders a week.

The addiction starts quietly — and the industry counts on that.

Every company claims dominance. We ignore the PR and go by the ledger.

As of September 2025, the hierarchy is not an opinion — it’s mathematics.

MetricBlinkitZeptoSwiggy InstamartMarket Share~50%~29–30%~23–25%Valuation~$13B~$5B~$11–12B (Group)Daily Orders600,000+500,000+450,000+Dark Stores1,000+700+557+Profit StatusAdj. EBITDA positiveHigh burnNegative margins

The real game isn’t groceries — it’s impulse-driven AOV (Average Order Value).

And I fell for it too.

If I needed something worth ₹60, I’d add items until the bill crossed ₹199 to “remove delivery charges.” After surge fees and service fees, I would pay ~₹200 anyway. The app didn’t waive the tax — it just trained me to spend more.

That is not convenience.

That is consumer conditioning disguised as savings.

You can’t make money delivering a ₹20 biscuit packet.

You make money when the customer — willingly — buys three more items they didn’t intend to.

My ordering behavior exposed what the data already knew:

I don’t switch apps for price — I switch based on item availability + distance. Swiggy gets most of my orders simply because the dark store is closer.

It’s not loyalty.

It’s logistics density disguised as customer love.

Tech influencers skip this part. I won’t.

Multiple Blinkit and Zepto dark stores were suspended in 2025 for fungal contamination and lack of pest control.

Speed isn’t free — it is paid for by skipped checks.

The CCI is investigating predatory pricing.

If proven, fines could reach 10% of global turnover.

Q-Commerce isn’t competing with kirana stores — it is eliminating them.

Everyone loves the rider until the order is delayed.

A Zepto rider told me something the apps won’t say publicly:

For COD, they must first pay the full amount online to the company, then beg the customer to pay them back. If the customer ghosts them, the system doesn’t protect them.

Algorithmic management with the responsibility of an employee and the rights of a freelancer — the perfect exploitation model.

Let’s drop the PR and look at the battlefield economically.

Blinkit achieved “density” — the holy grail of Q-Commerce.

Zomato gives it free customer acquisition. EBITDA is positive. AOV is highest.

They’re not selling groceries. They’re selling addiction with premium-SKU margins.

Zepto is Uber in 2016 — brilliant, burning money, loved by Gen-Z.

If they don’t IPO by 2026, they run out of runway.

Their only exit possibility: get acquired by Amazon or Flipkart.

Kirana stores are losing their most profitable sales (beauty, toys, gifting, packaged food).

They are left with only low-margin staples — a death sentence disguised as survival.

By my third or fourth order, I realized something:

I wasn’t paying for groceries.

I was paying for urgency.

The products were optional — the dopamine hit was the commodity.

Q-Commerce is not a convenience industry —

it is behavioral economics weaponized through supply chain efficiency.

Blinkit is winning today.

But in this industry, today’s king is tomorrow’s cautionary tale.

All claims in this article have been properly cited with inline hyperlinks. Click any highlighted text to access the original source. Key data sources include:

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs