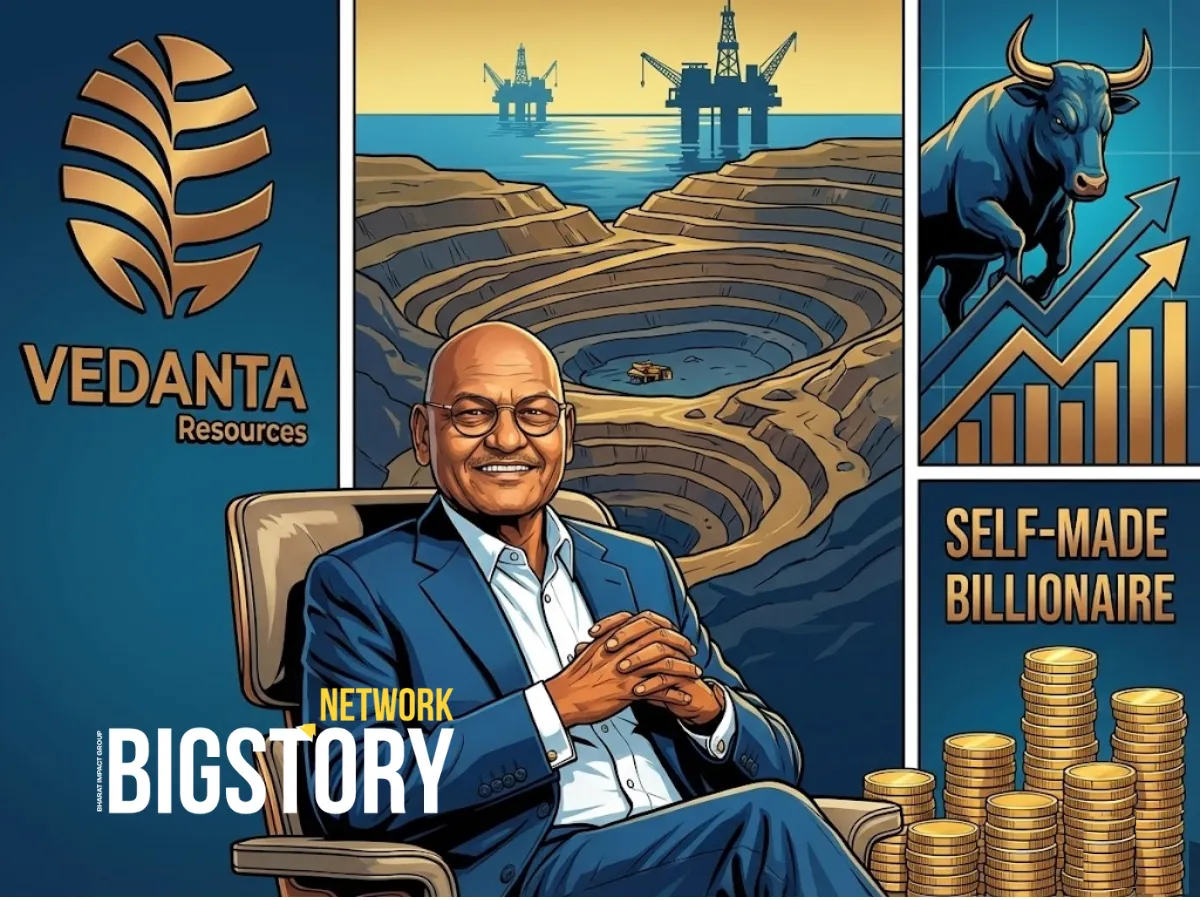

Anil Agarwal's inspiring journey from small-town ambition to building Vedanta, a global resources giant, driven by an "equal dream" for all.

Rashmeet Kaur Chawla

Rashmeet Kaur Chawla

India’s growth story is often told through scale: market capitalisation, global listings, billion-dollar valuations. What gets discussed far less is how that growth is built, and who it carries along in the process?

Anil Agarwal belongs to a generation of Indian industrialists whose rise coincided with liberalisation, globalisation, and the opening of Indian enterprise to the world. From modest beginnings in Patna to founding Vedanta, his journey fits the familiar arc of entrepreneurial ascent, but stopping there would miss the more consequential part of the story.

What distinguishes his trajectory is not just scale, but a consistent belief about ownership, participation, and inclusion. Across acquisitions, regional investments, and community infrastructure, his approach reflected a simple idea: long-term value is created when growth includes the people closest to production.

But at each stage of expansion, he returned to the same underlying question: who benefits when value is created, and who is left waiting?

And in a country still negotiating who truly participates in progress, stories like this are not about individual success. They are about the kind of economic future India chooses to build.

Anil Agarwal was born in 1954 in Patna, far from the centres of power that shape most industrial success stories. His father ran a small aluminium-conductor business which was merely enough to sustain a family but never enough to create security. What Agarwal gained instead was an early understanding of imbalance, how effort did not always translate into advancement, and how value was often created far from where decisions were made.

At nineteen, he left for Bombay with a suitcase and a tiffin box. With no safety net, he entered the scrap metal trade, buying and selling copper, aluminium, and zinc. Negotiating for material others had already written off, he learned quickly that value exists everywhere, but ownership does not.

What unsettled him was not hardship alone, but a recurring pattern: those closest to production rarely controlled outcomes. Labour created value, but rewards accumulated elsewhere and that tension became the question he carried forward.

Anil Agarwal had formed a belief that growth that excludes the people who create value is structurally fragile and that belief would soon be tested.

The belief Agarwal carried from the scrap trade did not stay abstract for long. It began to shape decisions as soon as survival gave way to expansion.

In 1976, he made his first decisive shift of trading to manufacturing by acquiring Shamsher Sterling Corporation, a producer of enamelled copper. It was a substantial risk. Manufacturing demanded capital, patience, and exposure to failure in ways trading did not. But it also offered something Agarwal had begun to value deeply: control over the system, not just participation within it.

When India liberalised its economy in the 1990s, markets opened and state-owned enterprises struggled to adapt. Where many saw dysfunction, Agarwal saw opportunity. His most controversial move came with the acquisition of BALCO (Bharat Aluminium Company), a loss-making public-sector unit burdened by outdated technology, labour unrest, and political resistance.

And instead of hollowing out the workforce, Agarwal focused on modernising systems while retaining local employees. Technology was upgraded, processes streamlined, and productivity improved but most importantly, livelihoods were preserved. The objective was not speed alone, but stability. Not extraction, but continuity.

This approach repeated itself across subsequent acquisitions—Hindustan Zinc, Sterlite Copper, Cairn India. Each expansion followed the same internal logic: value creation had to include the people closest to production, or it would not hold.

By the early 2000s, this philosophy had scaled into an enterprise of global relevance. In 2003, Vedanta became the first Indian natural-resources company to list on the London Stock Exchange. The milestone signalled India’s arrival on the global commodities stage but the structure underneath remained rooted in Agarwal’s original belief.

Growth was not an end in itself but it was a system that had to endure.

As the company expanded across minerals, metals, oil, and power, the question Anil Agarwal had carried since his early years continued to guide decisions: who participates when value is created, and who is merely affected by it?

As Vedanta expanded, the limits of conventional corporate responsibility became clear. Large-scale industrial operations inevitably reshape the regions they enter. For Agarwal, the question was not whether impact would occur, but who would control its direction.

The belief that growth must include those closest to production began to express itself beyond factories and mines. They scaled into education, healthcare, nutrition, and livelihoods and this was not positioned as charity, but as infrastructure.

Through the Vedanta Foundation, the company focused on long-term community development in regions historically treated as extractive zones rather than partners in growth. The intent was structural: intervene early, intervene locally, and intervene at scale.

One of the most visible expressions of this approach has been Nand Ghar, a modern reimagining of India’s anganwadi system. Designed to integrate nutrition, early childhood education, healthcare access, and women’s empowerment under one roof, Nand Ghar addressed a recurring gap Agarwal had observed as economic growth without human foundations does not sustain itself.

The same logic shaped Vedanta’s engagement in mineral-rich but underdeveloped regions such as Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan. Investment extended beyond extraction to roads, schools, healthcare facilities, drinking water, and vocational training. The objective was not visibility, but continuity by ensuring that economic participation outlasted individual projects.

Women’s participation became another deliberate focus. In sectors long dominated by men, women began entering roles in operations, safety leadership, and technical teams. Education and skilling were positioned as equalisers and not add-ons along with scholarships, training programmes, and rural entrepreneurship initiatives designed to make opportunity repeatable rather than exceptional.

However this expansion beyond the balance sheet was not without complexity. Natural-resource businesses operate under constant scrutiny, and Vedanta’s trajectory has included opposition, debate, and conflict. But what remained consistent was the underlying principle: inclusion was not a response to scale; it was a condition for it.

That conviction would increasingly define not just how Vedanta operated, but how Agarwal thought about legacy itself.

As Vedanta scaled into a global enterprise, questions of legacy moved from abstraction to intent. For Anil Agarwal, the issue was no longer how much could be built, but what would remain credible once scale was achieved.

In recent years, Agarwal pledged to give away 75 percent of his personal wealth to philanthropy, placing him among India’s most significant individual givers. The commitment drew comparisons to global initiatives like the Giving Pledge, but the motivation followed a more familiar internal logic. Wealth, in his view, was not an endpoint. It was a responsibility that arrived with scale.

Yet philanthropy was never positioned as a corrective to business. It was an extension of the same belief that had shaped his decisions from the beginning: systems last only when they include those closest to their creation. Education, healthcare, nutrition, women’s safety, and skilling were not treated as parallel efforts, but as long-term investments in social participation.

This perspective reframes how success itself is measured. Not by valuation alone, Not by global presence, but by endurance, by questioning whether growth continues to hold when leadership changes, markets shift, and scrutiny intensifies.

Agarwal’s journey does not argue that capitalism must abandon efficiency to become equitable. It argues something narrower, and more demanding: that efficiency without participation eventually erodes its own foundation.

Anil Agarwal’s BIGSTORY is not about rising against odds. It is about refusing to accept a system where effort and ownership are permanently separated.

His belief is simple, but uncompromising:

Growth that does not include the people who create value cannot sustain itself.

From scrap trading to global enterprise, from factories to communities, that idea has been tested repeatedly and sometimes contested, often scrutinised, but never abandoned.

This is why his story matters.

Not because it proves that anyone can rise but because it asks a harder question: what kind of systems are worth rising within?

In a country still defining the terms of its economic future, Anil Agarwal’s journey stands as a reminder that inclusion is not a by-product of growth.

Q1. Who is Anil Agarwal?

Anil Agarwal is the founder of Vedanta, one of India’s largest natural-resources conglomerates, known for its operations across metals, mining, oil, and power.

Q2. What makes Anil Agarwal’s journey different from other industrialists?

Unlike many traditional business success stories, Agarwal’s journey is defined by a consistent belief in ownership, participation, and inclusion—shaping how Vedanta scaled across regions and communities.

Q3. What is Vedanta’s approach to inclusive growth?

Vedanta’s model focuses on integrating community development, education, healthcare, and livelihoods alongside industrial operations, treating inclusion as infrastructure rather than charity.

Q4. What role did BALCO play in Vedanta’s growth?

The acquisition of BALCO marked a key turning point, where Vedanta prioritised system modernisation while retaining the workforce—reflecting Agarwal’s belief in continuity over displacement.

Q5. Why is Anil Agarwal’s story relevant today?

In an era questioning who benefits from economic growth, Agarwal’s journey highlights a model where long-term value depends on participation, not extraction alone.

On the 75% Wealth Pledge & Philanthropy:

On the LSE Listing (2003):

On the BALCO Acquisition & Modernisation:

On Community Infrastructure (Nand Ghar):

On Anil Agarwal’s Early Life & Career:

Sign up for the Daily newsletter to get your biggest stories, handpicked for you each day.

Trending Now! in last 24hrs

Trending Now! in last 24hrs